The wild X-Men FPS you were never meant to play

How a fan project became Marvel’s first superhero first-person shooter… where you kill the X-Men

Credit: Zero Gravity Entertainment

In 1997, a game was released that let you step into the shoes of a Magneto-built cyborg and wipe out an army of mutant clones. It was loud, bloody, confusing, and brutal.

It was also Marvel-approved?

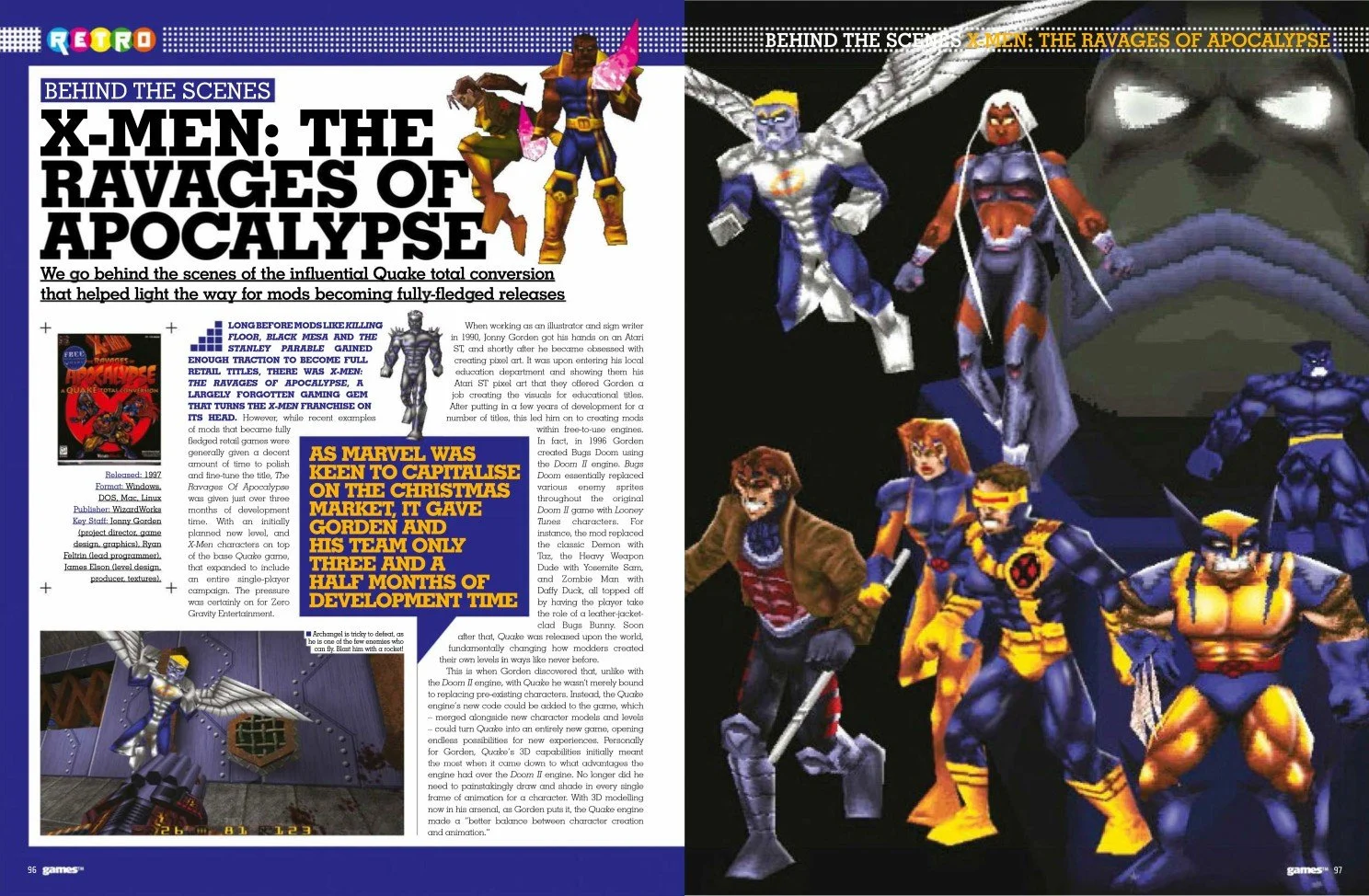

That game was 𝗫-𝗠𝗲𝗻: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗥𝗮𝘃𝗮𝗴𝗲𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗔𝗽𝗼𝗰𝗮𝗹𝘆𝗽𝘀𝗲, a standalone Quake total conversion that flipped the superhero formula on its head. Instead of playing as Wolverine or Cyclops, you fought against them. Or at least, their twisted, cybernetic clones. Powered by the original Quake engine, it became the world's first superhero first-person shooter and earned a Guinness World Record.

And somehow, almost no one remembers it.

Built by Modders, Backed by Marvel

Credit: Zero Gravity Entertainment

Johnny Gordon wasn't a AAA developer. He was an Australian illustrator and sign writer who got into pixel art and 3D modeling through the Atari ST and Doom II. After building a 𝗟𝗼𝗼𝗻𝗲𝘆 𝗧𝘂𝗻𝗲𝘀 mod (Bugs Doom II), Gordon dove into Quake, excited by its 3D possibilities and modding flexibility. One of his first experiments? Making Storm from the X-Men.

𝗧𝗵𝗲𝗻 𝗰𝗮𝗺𝗲 𝗪𝗼𝗹𝘃𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗲.

"I thought the Fiend's behavior would work really well for him without having to change any QuakeC files," Gordon later said. "So he ended up being the first playable character."

He envisioned multiplayer mayhem. Replacing models. Swapping weapons. Rebuilding the X-Mansion. But it was just a fan project, until it went viral on early modding forums and caught the attention of a game industry insider named Kyle Bousquet, who had ties to Marvel.

Within a week, Gordon pitched the concept. And then something shocking happened: Marvel called back. So did id Software.

A Licensed Game in 3 Months

Marvel said yes, but with a catch. They wanted it on shelves by the 1997 holiday season. Gordon had just over 90 days to go from fan mod to full commercial game.

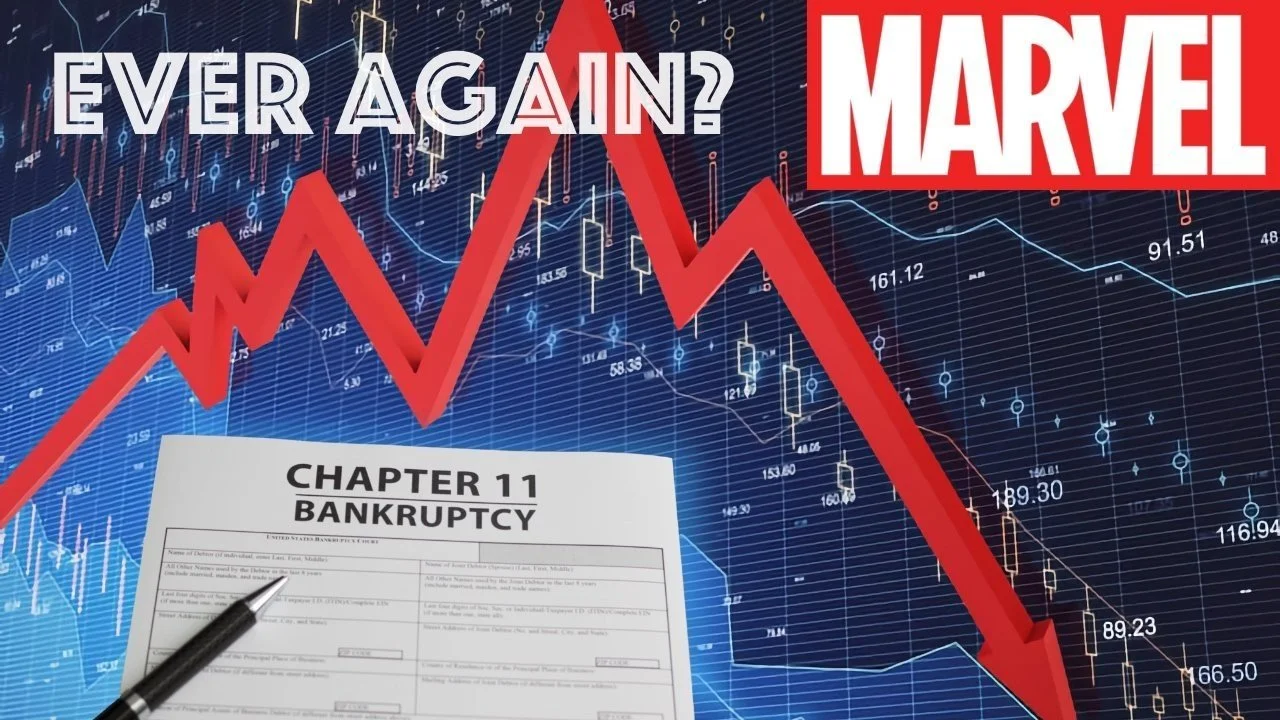

id Software agreed to a commercial release under one condition: the game had to feature entirely new levels, not just reskinned assets. Marvel, on the other hand, was in a financial crisis. The company had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1996, and its core business, comic book publishing, was collapsing. The speculator bubble had burst.

Credit: Culture Slate

Throughout the early '90s, fans had bought up boxes of first issues, convinced they'd be worth a fortune in the future. But the market became oversaturated, demand dropped, and resale value never materialized. With sales plummeting and no stable financial base, Marvel began licensing its characters to stay afloat, first to video games, then to movie studios.

Marvel thought, how hard could it be to replace characters in a game in three months? The Ravages of Apocalypse was riddled with scope creep and crunch to generate revenue from one of their most valuable brands: the X-Men.

Gordon pulled together a remote team of 26 developers. They worked from home, across time zones, sprinting to build an original 10-episode FPS starring clone versions of the X-Men. Marvel even assigned an executive producer and approved the concept of bloody mutant-on-mutant violence.

They requested a few lore tweaks: Terminus was replaced with Mr. Sinister. Dr. Doom became Magneto. Clones were the justification for why you were fighting the X-Men instead of playing as them.

For Gordon, it was all about pushing the limits of what Quake could do.

"We were doing things with the Quake engine it was never built for," he said. "It was a massive struggle. Everyone was working at least 20 hours a day, seven days a week."

What Went Right (and Wrong)

The game shipped on December 5, 1997. It featured:

14 playable clone characters including 𝗖𝘆𝗰𝗹𝗼𝗽𝘀, 𝗥𝗼𝗴𝘂𝗲, 𝗚𝗮𝗺𝗯𝗶𝘁, 𝗝𝗲𝗮𝗻 𝗚𝗿𝗲𝘆, 𝗣𝘀𝘆𝗹𝗼𝗰𝗸𝗲, 𝗖𝗮𝗻𝗻𝗼𝗻𝗯𝗮𝗹𝗹, 𝗦𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗺, 𝗪𝗼𝗹𝘃𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗲, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗺𝗼𝗿𝗲.

Credit: Zero Gravity Entertainment

Custom weapon sets were integrated into the cyborg protagonist.

Unique powers and AI for each clone opponent.

A multiplayer mode and third-person patch were released post-launch.

But Ravages of Apocalypse was rough. Reviewers called it too hard. Weapons shared the same ammo pool. Rogue and Cannonball were nearly unkillable. Key items often failed to spawn. And the premise: killing the X-Men over and over, confused players expecting to be the heroes.

Yet even in its chaos, it carved out a place in gaming history. This was the first superhero FPS. A Marvel-licensed game born from fan creativity and late-90s ambition.

Credit: Zero Gravity Entertainment

The Forgotten Legacy

By 1998, the game faded into obscurity. A planned sequel was scrapped when Activision secured an exclusive Marvel license. In 2006, Ravages of Apocalypse was re-released as freeware. Its source code is still online, open to modders and historians.

Gordon looks back on it with pride.

"We made the best game we could under impossible circumstances," he said. "It was fun to play as the X-Men in multiplayer, and the single-player held together surprisingly well."

It wasn't perfect. But it was real. And for a brief moment, a fan project turned commercial game changed what was possible in both superhero gaming and the modding community.

Final Thoughts

This wasn't a AAA launch. It wasn't polished. But it mattered.

Before Spider-Man, Guardians of the Galaxy, or Midnight Suns, there was a gritty, offbeat game built on the Quake engine where you could flamethrower Cyclops and rocket-launch Wolverine. A game that almost no one remembers, but helped prove that mods could be more than side projects.

Sometimes, the weirdest games have the most incredible stories behind them.

𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗲 𝘆𝗼𝘂 𝗽𝗹𝗮𝘆𝗲𝗱 𝗶𝘁? 𝗦𝗵𝗼𝘂𝗹𝗱 𝗠𝗮𝗿𝘃𝗲𝗹 𝗲𝘃𝗲𝗿 𝘁𝗮𝗸𝗲 𝗮 𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗸 𝗹𝗶𝗸𝗲 𝘁𝗵𝗶𝘀 𝗮𝗴𝗮𝗶𝗻? 𝗪𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗼𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗳𝗮𝗻 𝗺𝗼𝗱𝘀 𝗱𝗲𝘀𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗲 𝗮 𝘀𝗲𝗰𝗼𝗻𝗱 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗲?

Check out more of my article: https://www.linkedin.com/in/bubbagaeddert/recent-activity/articles/

Subscribe to Patch Notes - The Stories and History Behind Video Games and Esports